Some years ago I saw a an 11 year-old boy having difficulty blowing his nose only on one side. A soft grayish mass protruded from his right nostril whenever he blew it hard. And he’d suck it back in to make it disappear. Being a kid, he thought it was an alien, like the one in the movies, though harmless since it had no teeth. Naturally his mother freaked, but his dad found it amusing. I believe he wanted to sell tickets at dinner parties or rent him to the travelling circus. Since no circus was coming to town and Sigourney Weaver was unavailable, Dad wisely agreed with Mom to bring him to an ENT doc. I was the lucky guy.

Nasal polyps are common problems ENT docs encounter. Yet there are unusual presentations, real doozies that make the job quite interesting to say the least. One such phenomenon is the antrochoanal polyp.

A mouthful of words indeed, but we medical folks love complicated nomenclature—another fancy term for “a naming system.” There’s a rhyme and reason for the term “antrochoanal.” A polyp is an abnormal mass filled with inflammatory tissue; check Nasal Polyp: Fun Times for All to tickle your noggin on that thrilling topic. Polyps in the nose tend to arise from the paranasal sinuses. In this case, the maxillary sinus is involved. The airspace that comprises this sinus is also called the maxillary antrum. Antrum is another name for “cavity.” If you must know more about sinuses, then Paranasal Sinuses: What, Where and Why has it for you.

Inflammation of the sinuses can cause swelling of the mucosa—the pink tissue that lines the sinus spaces as well as the rest of the nose. This swelling can progress, leading to swollen tissues that become polyps, and then project through the ostium (natural opening) of the sinus and into the nasal cavity. Sometimes the polyps get so large they either: (1) protrude out from the nose, making it visible to everyone facing you (imagine a bald, faceless alien popping out of your nose and you’ll get the idea) or (2) drop farther back into the choana, the most posterior portion (back part) of the nasal cavity. I’ve seen presentations of both.

So a polyp arising from the maxillary sinus antrum and extending far to the back of the nose into the choana is called an antral-choanal polyp, and for some reason the term contracts further to form antrochoanal (which might be a job-security issue for linguists who contrive this stuff).

I’ve had two cases in kids. One was a 13-year-old girl who presented with a throat mass noted by her pediatrician. It looked gray and unusual for a mass arising from the throat. I got to thinking (which I must do more often, I’ve been repeatedly told) that this might actually be arising from the back of the nose called the nasopharynx or even farther forward from the nasal cavity or sinuses. The nasopharynx is above the soft palate and uvula, and is the space that separates the choana of the nose from the oropharynx (or throat). I ordered a CT (computed tomography) and lo and behold there it was--a mass extending from the maxillary sinus and travelling backwards in the nose, beyond the choana and nasopharynx and continuing onward behind the soft palate and uvula and downward into the throat. I took her to surgery and removed the monster, opened cleaned out the maxillary sinus from where it arose. This was many years ago and I regret not taking photos, for this was a rarity, one worthy of wall-mounting and tremendous bragging potential.

The second case was the young boy mentioned at the beginning. Ironically, his initials were the same as the girl’s above, but for privacy reasons, HIPAA and all that jazz, I can’t elaborate further. Only his polyp would protrude from his nostril when he blew it hard, whereas the girl’s didn’t. His CT is below:

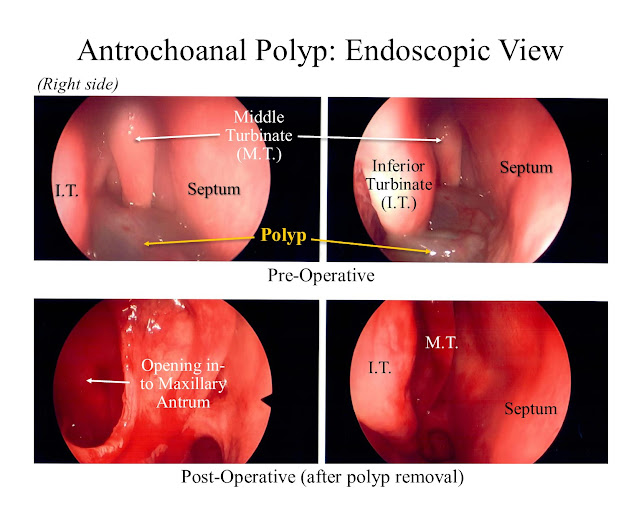

The photo below (through an endoscope during surgery) is actually from this same lad recently as an adult. The polyp recurred 8 years later and he presented with the same symptoms, though with additional years of matured wisdom he understood it wasn’t an alien.

Both patients recovered well with little to no pain, and their symptomatic improvement was immediate. The second surgery with the young lad also went smoothly and he had little to no postop pain, needing no pain medication. Though I scraped the maxillary antrum well in each case to remove the inflamed lining tissue, uncommon events such as recurrence can still occur with this otherwise benign and uncommon phenomenon.

©Randall S. Fong, M.D.

For more topics on medicine, health and the weirdness

of life in general, check out the rest of the blog site at randallfong.blogspot.com

Comments

Post a Comment