You’ve been noticing difficulty hearing in only one ear. Or you find your hearing is declining in both but one ear seems worse than the other. You might have something more than run-of-the-mill ear wax or a foreign body plugging your ear canal, such as that long-lost piece of jewelry you blamed your three-year-old from taking.

Asymmetric hearing loss is the term we use for this type of problem, and it can be an omen of a more ominous cause. As such, you oughta get it checked.

To evaluate asymmetric hearing loss, you first, of course, need to see a doctor. An examination of your ears is required, and sometimes the rest of the structures of your head and neck, esp. if otitis media or a middle ear effusion is found, to rule-out other unusual findings such as a growth/tumor in the nasopharynx (back of the nose).

For an explanation of the different types of hearing loss, see the aptly titled post, Hearing Loss: Explanation of the Different Types.

By the way, the concept of immediate or sudden hearing loss is a different matter altogether, and this article focuses on hearing loss that is gradual in onset or progressively worsening with time.

Let’s say your physical exam is normal and your hearing loss is sensorineural, meaning the source is from the inner ear (cochlea) or acoustic nerve leading from the cochlea to the brain (link to anatomy). We clever docs like to abbreviate things, and so we’ll use the acronym ASSNHL for asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss.

The next step is a hearing test (audiogram). Part of the audiogram is a graph showing hearing level (volume or loudness) on the vertical axis and hearing frequency (pitch) on the horizontal access. Below is an audiogram from a patient with normal hearing in both ears.

|

| Audiogram: normal |

Notice that the hearing level on the vertical scale gets higher (the sound stimulus becomes louder) as one moves downward on the graph, which is the opposite of other types graphs you’ve likely seen in the past.

We’ll use a few actual case studies to illustrate ASSHL.

Case 1 is a Russian woman in her 60s with gradual

right-sided hearing loss over the past 5 years.

Her ENT exam was unremarkable. Here’s

her audiogram (Audiogram 1)

|

| Audiogram Case 1 |

This is a significant asymmetric hearing loss, where the right ear is much worse than the left. Hearing does decline as we age, but both ears decline at the same rate, and so the hearing levels between the right and left ears should be similar. This clearly is not the case here. Of note: Only pure-tone testing was done. Speech testing could not done since this uses an English word list, and she was Russian-speaking only, requiring an interpreter.

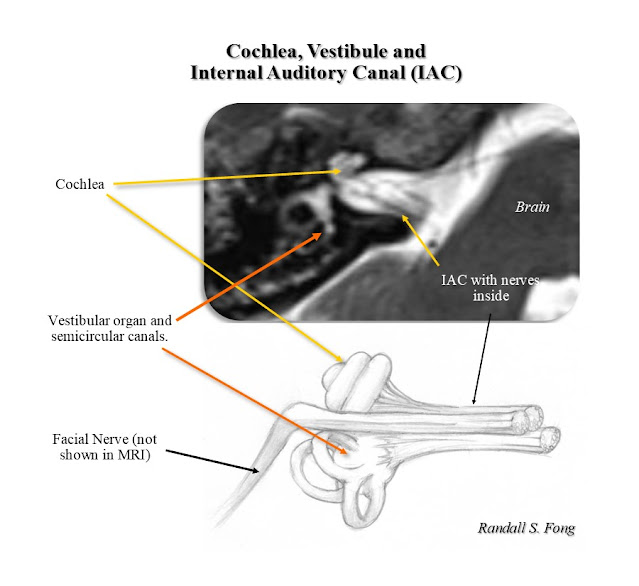

In this case, we must search for potential causes such as a tumor compressing the cochlear nerve (nerve of hearing). The best means to look for such a problem is with an MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). Figure 1 shows a normal MRI. Figure 2 shows a closer view of the IAC (Internal Auditory Canal) which is a canal within the temporal bone that encases the nerves that lead from the cochlea and vestibular organ to the brain.

|

| Figure 1 |

|

| Figure 2 |

|

| Figure 3 |

Case 2 was a 16 year-old male with left sided hearing loss of gradual onset. He also experienced problems with his balance, feeling unsteady for about a month. His mother thought he was merely a clumsy teen, since he’d always been a bit unsteady, but lately had worsened. He also wasn’t hearing well, and she realized he wasn’t just being a teenager and simply ignoring poor Mom and Dad. That’s when she brought him to us.

|

| Audiogram Case 2 |

Notice the normal right hearing but the left shows a profound hearing loss. He could barely detect any sound in that left ear.

An MRI was ordered (Figure 4). We were shocked to find the presence of not one, but TWO acoustic neuromas, which were quite large. In fact, the right was larger (up to 4.5 cm) though it was not compressing the acoustic nerve but was extending lower into the CPA. Thus his hearing was preserved in that right ear. The smaller left tumor was involving the nerves in the IAC and measured up to 2.8cm. These also were compressing his brainstem and cerebellum, and thus the reason for his unsteadiness. The cerebellum is the part of the brain in the back of your head that helps control gait and balance. It also may have been affecting the vestibular nerves in the right IAC—the vestibular organ in the inner ear also helps with balance.

|

| Figure 4 |

He required surgery done in stages, removing the largest tumor on the right, and later removing the left side done later.

In many cases for smaller ANs, surgery is not always needed. Sometimes treatment is done with a Gamma Knife, which is radiation treatment focused onto a small target. Many times smaller ANs are merely followed with MRI scans done once a year, reserving surgery for those that are increasing in size. Often times the MRI is normal and no tumor is noted, and the explanation for the ASSHL is unknown. In any event, as these two cases demonstrate, ignoring ASSHL is not advisable. Don’t wait until your spouse grabs you by your ear (your good one) and drags you to the doctor; you don’t want ear pain on top of your hearing loss, not to mention the embarrassment being dragged into the doc’s office.

©Randall S. Fong, M.D.

For more topics on medicine, health and the weirdness

of life in general, check out the rest of the blog site at randallfong.blogspot.com

Comments

Post a Comment