No joke with the title. The design of the human body never ceases to amaze. For instance, the facial skeleton serves functions other than creating your natural good-looks, that certain aesthetic appeal which supposedly attracts others to you, especially when searching for a mate to propagate the species. Together with the sinus spaces deep within, the bones of the face also protect the brain.

“Protect the brain? How much have you been drinking?”

I get this response from time to time, sometimes in social gatherings, from non-medical folks, a few med students, residents (and a few docs) when I’ve mentioned this in the past.

Yes, the face protects the brain. No, it’s not meant to charm your way from unpleasant mental activities such as studying and going to school. Rather, the face acts as a natural shock-absorber when the force of trauma finds its way upon your smiling countenance, deservedly or not. Either evolution, the Almighty or a combination of both determined the brain is more important than one’s expressive face--though there are those who wouldn’t benefit from this insurance, using their brains as a last resort or not at all.

The face attaches to the rest of the

skull by a system of buttresses.

These are thicker struts of bone formed as the face grows and develops

from infancy to adulthood. It is

believed these buttresses were initially designed to withstand the forces of

mastication or chewing (Figure 1).

The jaw muscles are some of the most powerful in the body, serving to

tear, grind and rip into food with tremendous force, particularly in our primal

days as hunter-gatherers. Strong bone is

necessary for this mandatory survival function.

Yet the buttresses also serve to disperse blunt-force trauma, such as a

falling off a cliff and landing upon one’s face, a blow with a large club from

a jealous spouse or, later in the developed world, a high-speed motor vehicle

accident.

Figure 1 Forces of mastication

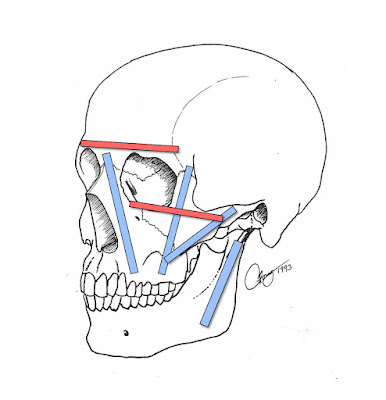

Figure 2 shows the location of these buttresses. The blue bars represent vertical buttresses, which maintain the face’s vertical height. The red bars are horizontal buttresses which serve as cross-members, adding additional structural support and strength to cope with the loads applied to the face.

Figure 2 Buttresses of the facial skeleton

The face fractures in fairly predictable ways along these buttresses. Figure 3 shows variations of mid-face or maxillary fractures, called LeForte fractures; the figure shows the locations of these fractures (designated as Type I, II, III from bottom to top). Take note that the facial bones and skull are fused together at sutures, natural fissures between bones. These sutures separate and fracture more easily than solid bone, allowing the facial skeleton to more easily fracture and displace much of the force away from the brain.

The sinus spaces around the

buttresses also help with the fracturing process; the bones surrounding some of

the sinuses are quite thin and easily fracture.

Overall, this helps dissipated blunt force away from the cranium, that

large space in your head that holds your brain (arguably, some brains are

bigger than others). Our face may be

crushed, pushed inward or outward or a combination of both. But heck, that’s the reason we have facial

trauma surgeons!

Figure 3 LeForte fractures

Figure 4 shows a malar-complex (or zygomatic-malar complex fracture or ZMC fracture, or let’s just say it’s a cheek bone fracture). The ZMC is solid bone. It fractures where it attaches itself onto: 1. the thinner bone that forms the maxillary sinus, 2. the zygomatic arch which attaches the ZMC to the side of the head in front of the ear, and 3. the frontozygomatic area where it attaches to the site of the eye socket. There are natural sutures at all three sites.

Figure 4 Zytomatic-malar complex (ZMC) fractures

This facial shock absorption requires fully developed paranasal sinuses. This allows broken bone to move into or out from the sinus spaces. Think of an empty beer can being compressed like an accordion. When crushed, it acts as a cushion when significant force is applied, such as standing upon the can or smashing it upon your forehead (only drunk guys tend to do this. Forgive us; it’s that short Y chromosome, the one carrying the genes for common sense). Imagine doing this with a solid metal can; it would hurt like hell, the can wouldn’t compress, transmitting all that force to the brain. The poor guy would knock himself unconscious. Likewise, if the face were completely solid, all of the force directed to the face would transmit directly to the brain.

In young children, the sinuses are not fully developed, and the face is relatively smaller compared to the cranium. As the child ages towards adulthood, the face and sinuses grow at a faster rate than the cranium, such that the face/cranium ratio is greater than it is in childhood. This is the reason adults in blunt-trauma accidents suffer more facial fractures and less brain trauma compared to young children, who suffer less facial trauma but higher skull fractures and/or brain injury. Developmental biology also never ceases to amaze.

So go out and have some fun, but don’t ask for trouble and don’t try to test the shock-absorptive qualities of your face.

©Randall S. Fong, M.D.

For

more topics on medicine, health and the weirdness of life in general, check out

the rest of the blog site at randallfong.blogspot.com

Comments

Post a Comment